Discover more from Dragon's Den Investing

There is no geopolitical relationship more important to the future of humanity than that of the US and China. With the relationship at its best, competition makes both countries and the world richer; yet at its worst, conflict unlike anything since World War II could result. As someone who has lived and worked in China over the last 20 years, this issue is deeply personal, and it’s been painful to have gone from an optimistic to a pessimist on the topic. In this week’s article I will highlight why I am so down about the US-China relationship, and how I believe a stock portfolio can be at least partially insulated from the fallout of a conflict over Taiwan.

The Unquiet Past:

When Chiang Kai-Shek ruled China during World War II, his journal entries began with “Avenge Humiliation” in the header - every single day for nearly 20 years. It’s difficult to overstate how much an impact the Century of Humiliation, that started with the first Opium War in 1839 and ended with Mao Zedong declaring in 1949 that “The Chinese people have stood up,” still has on Chinese leadership and society today. Because of the foundational experience of having its territory carved up and divided amongst those with more power, the Chinese understandably have a hyper-sensitivity to any perceived slights on their territorial claims.

Every country has certain “red lines,” meaning that which it will never compromise on. For the Communist Party that rules China, there’s no red line brighter than Taiwan and its claim over the island as an integral part of the PRC (People’s Republic of China). As an American, the best way I can think of comparing PRC views on the importance of territorial integrity is by comparing it to the first or second amendment of the US Constitution. If an international organisation or foreign country told Americans to alter these amendments, we would never compromise.

All that said, the reality is that Taiwan today is its own country with a formidable military, dynamic economy, and vibrant democracy. Why did the PRC allow this to happen if its such a red line? Simply because until now they’ve lacked the power to do much about it. Since 1950 when Truman sent the US Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Strait to defuse tensions, the US has essentially had a security guarantee for the island under a policy of “strategic ambiguity”. Along with heightened tensions, cracks have begun to form in the policy that has held peace together for the last 70 years.

The Return of History:

There was a moment that’s always stuck with me, when I was with a group of Chinese friends during the 2012 Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute. I brought up not understanding why some small uninhabited rocks were such a big deal to a rising power like China (and that China should use its political capital for more important issues) - to which I received in response raw emotional pain and a lecture on why in historical context these islands matter so much. Even as a student of China discussing politics with worldly post-graduates studying abroad, I had misunderstood how central and emotional the issue of territorial integrity is for most Chinese people. In short, Japan nationalising a disputed island was a humiliation that reopened wounds of the past that are to this day still unhealed.

I bring this experience up not only because it was instructive, but because it happened at a time of relative calm in international relations. In the next year, two world changing events would occur that set the next 10 years in motion:

The Edward Snowden leaks that revealed the US had access to Chinese systems that went deep into infrastructure, companies, and the military.

The ascent of Xi Jinping to power in China.

The Edward Snowden leaks did irreparable harm to any trust the Chinese had for the Americans. It set into motion the push to completely decouple hardware systems from American technology, which could be seen in the “Made in China 2025” announcement of 2015. MIC 2025 was a total shock to Western companies and governments, and played a pivotal role in many of the sanctions first introduced by the Trump administration.

Xi Jinping’s ascent to power was originally seen as a hopeful sign for US-China relations, yet this hope would soon disappear for those who thought the status quo was to remain unchanged. This was a man that viewed himself as a historical figure, whose only rival in modern Chinese history was Mao Zedong, and whose thought itself became interwoven into the fabric of society. There were several pivotal events relevant to our topic which struck many as a new turn in Chinese history.

The scale of ever present “anti-corruption” purges that have netted approximately 2.3 million government and military officials. There was certainly a fair amount of corruption in China prior to Xi, but he has also used this campaign as a way of stifling dissent and installing officials in important positions who are completely loyal to him. The PLA (People’s Liberation Army) reports directly to Xi, and its leadership consists of complete loyalist who would not dare push back on orders.

Shifting priorities from becoming rich to becoming strong. Xi sees his time in office as a new era of strength and historical righting of past wrongs. He sees his recent predecessors as focused on lifting China out of poverty through a willingness to compromise on core interests, whereas he will no longer acquiesce to foreign pressure if the trade-off is merely a marginal hit to GDP. No longer is GDP growth the primary driver of China’s decisions.

Removal of term limits in 2018. Even among my Chinese friends who lean more nationalist, Xi removing term limits so he would be leader in perpetuity was a complete shock. A mark of any successful country regardless of its political system is its ability to transition power peacefully and predictably between leaders. Leadership in perpetuity centered on one man has not happened since Mao - and people remember the chaos that ensued. Related to the first point above, the vote to confirm this change in China’s congress was 2952 to 0.

2019-2020 implementation of national security law in Hong Kong, and violent suppression of protests. The One Country Two Systems policy ended with Xi, and it was clear that any former territory of China once under China’s rule would follow China’s laws completely. This ended the potential for Taiwan to someday fall under the same One Country Two Systems policy that had been successful for Hong Kong and Macau. Perhaps the only peaceful re-unification pathway.

For those who want more on Xi’s life and ascent I highly recommend an Economist podcast called The Prince.

Change in America:

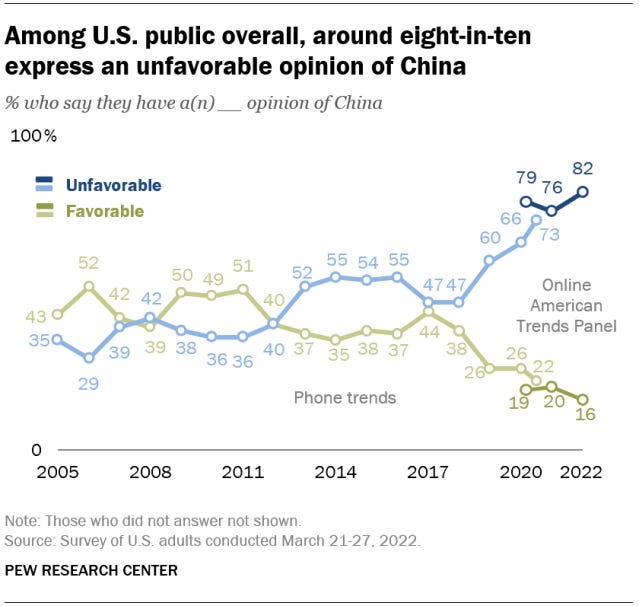

With all the changes in China over the last decade, America and particularly its policy towards China has evolved drastically. The Trump administration simply took the first official step with its trade sanctions on China, but broader trends have now aligned the American public and both political parties to see China as the top strategic threat. COVID completely destroyed the last shred of trust and goodwill America had for China, and China’s obfuscation in investigating how COVID spread will have lasting effects on the American public/politicians to assume the worst about its chief rival. The Biden administration has continued and in many cases increased the trade restrictions and sanctions of the past administration.

At the same time, America internally has seen a gradual rise and greater potential for political instability. The 2024 election will be tumultuous at best, with each party’s candidate trying to one-up the other in terms of toughness on China. Trump still has a bone to pick with China, especially considering that he would have won re-election if not for COVID. Biden will be 86 years of age at the end of his 2nd term, and Trump (if elected) would be 82. A distracted and chaotic America will at minimum increase the odds China takes precarious steps towards Taiwan. A resentful America will increase the risk of miscalculation and escalation in response.

America has also begun to prepare itself for the eventuality that China will be militarily powerful enough to take Taiwan if it chooses to. The CHIPS act, which incentives semiconductor manufacturing in the US will lessen reliance on Taiwan, and essentially remove the primary reason for realists and America First politicians in the US to defend Taiwan. Vivek Ramaswamy, a leading republican candidate who channels Trumps views, has outlined the idea that we should defend Taiwan only until the US is able to manufacture its own advanced semiconductors. I suspect this view will gain momentum as the potential alternative for a war-weary America becomes clearer.

The Law of the Jungle:

There is a recent argument in foreign policy circles around whether allowing Russia to win in Ukraine gives China the green light to invade Taiwan (and therefore the US and its allies must continue funding Ukraine to deter China). This argument is less clear cut than many would hope for as there is now essentially a stalemate in the war with either side unlikely to make near-term progress. What I find most instructive in the Russia-Ukraine conflict for the potential China-Taiwan conflict is how the rest of the world has reacted to a nuclear-armed dictatorship invading a smaller neighbouring democracy.

Surely western sanction have been painful for the Russians, but several facts remain:

Vladimir Putin is still in power and relatively popular with Russians.

The Russian economy has stabilised and is now growing.

Most countries are still trading with Russia, even some US allies. Countries do what’s in their best interest, regardless of the values/actions of the other side.

Western allies have decided not to put troops on the ground in Ukraine.

For Xi Jinping, would similar consequences while delivering Taiwan’s return to the Mainland really be a deterrent? Unlikely. The calculation then must be, would the US and its allies join the fight if China invades Taiwan? If not, then it’s worth it for Xi Jinping. If so, status quo is preferred as the cost would be catastrophic. Biden has let slip on multiple occasions, in a seemingly offhanded way, that he would defend Taiwan with American troops if China attacked (contradicting the official policy of strategic ambiguity). Whether or not this is a bluff is of immense importance to the risk calculation from China’s point of view. While the US maintains a thin veneer of credibility in its defence of allies like Taiwan, this credibility largely depends on if Ukraine continues receiving support and holds the military line. The eventual suing for peace that happens in all war, as Ukraine is forced to give significant concessions to Russia for its survival and the US is poorer for it, will be a boon for those in China clamouring for forced reunification with Taiwan. The war realities on the ground in Ukraine and the internal politics of the US trend towards this eventuality, with many republicans already trying to separate out Ukraine aid from larger bills. A war weary America tired of wasting money on foreign wars while people are discontented at home, combined with the eventual lack of reliance on Taiwan for its semiconductors leads to a lower probability of the US coming directly to Taiwan’s defence with its own forces. At the same time, China is building ships at a furious pace to prepare for the opportune moment. The geopolitical realities and internal politics of both sides outlined above leads me to conclude that China is likely to move on Taiwan in the next 2-10 years.

A Note on TSMC’s Role in War Gaming Potential Conflict:

Some technology and foreign policy observers point to TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), and argue that China’s motivation for invading Taiwan boils down to control over the most advanced semiconductor facilities in the world. I hope the above analysis dispels this thought. My view is that China’s core interest lies in territorial integrity, and Taiwan is the top priority in achieving this long running interest. Nothing will stop them from seeking it, and Xi Jinping as a man of historical consequence wants more than anything to be remembered as the one who made China strong and fully reunited the country under his banner. The idea that TSMC is more important than this ideological belief is absurd, and furthermore any war over Taiwan would likely render TSMC’s facilities unusable or destroyed.

Stock Portfolio Implications:

This week Xi visited the US for the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) summit. By all accounts the meeting with Biden was a success for both sides, and renewed engagement on military communication, climate change, AI, and fentanyl were agreed upon. China’s economy is currently struggling, so Xi is looking to placate foreign investors after direct investment into China fell off a cliff this year with many companies de-risking from the Mainland. I anticipate this short-term trend will continue over the next year while Xi focuses on stabilising China’s economy, and Biden tries to prevent another conflict from breaking out before his re-election bid. Tensions will rise again around and after the US election. A risk seeking investor could put money into stocks like JD 0.00%↑ , PDD 0.11%↑ and BABA 0.00%↑ with a 6 month time-frame in the hopes of selling out before election fever sets in. I find this too risky, as a myriad of events (a military accident, another US politician visiting Taiwan, Taiwan election in January, etc.) could at any moment send relations spiralling again.

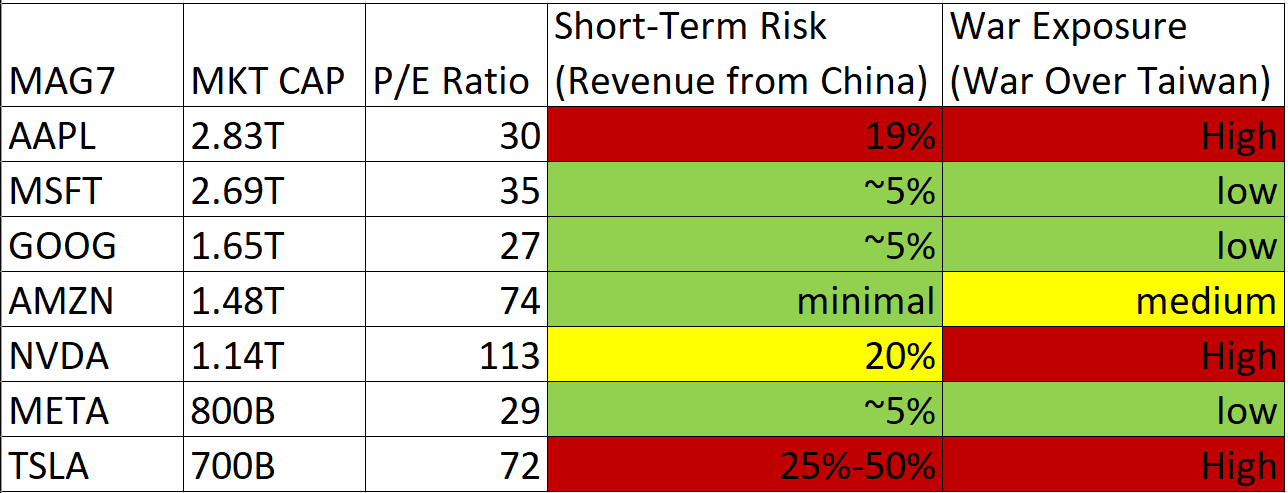

As a longer-term growth investor picking individual stocks, I now only put stocks into my watch list with low China exposure both in the short-term (as highlighted in last week’s article) and in the war risk scenario. This is because I think there is asymmetry in how companies with China exposure are valued relevant to the risk China poses to them. Short-term revenue risk lies in the eventuality of China favouring domestic champions, especially when foreign manufacturing leaves China (due to geopolitical realities and shareholder pressure). War exposure risk lies in being unable to move products produced in China out of China to the rest of the world, and more importantly being unable to use semiconductors manufactured in Taiwan. The conflict over Taiwan will be the most important world event in the next 10 years, so it must be at the forefront of every risk calculation for an investor. For perspective, let’s take a cursory overview of the magnificent 7 tech stocks:

From the above we can see that MSFT 0.04%↑ GOOG 0.11%↑ and META -0.15%↓ are stocks I would consider for long-term investment. AMZN 0.00%↑ and NVDA -0.12%↓ could be short-term investments (under 2 years); but AAPL 0.05%↑ and TSLA -0.18%↓ are far too risky for someone who believes conflict is more than likely. It’s possible that Apple and Tesla will shift more production outside of China in the coming years, but until then my view on these stocks is unlikely to change… and even if they do shift production, they have such massive revenue reliance on China that it will be hard to make up elsewhere.

How can we test this thesis? Let’s create a portfolio of $100,000 invested today (11/17/2023) at close of market prices with four separate scenarios:

Portfolio #1 - Index approach - $14,285 divided evenly among the MAG7

Portfolio #2 - China risk on (anti-thesis) - $50K divided evenly among Apple and Tesla

Portfolio #3 - China risk off (thesis) - $33.3K each for Meta, Microsoft, and Google

Portfolio #4 - No war, short-term revenue risk avoidance only - $20K divided between Meta, Microsoft, Google, Nvidia, and Amazon.

Obviously there are many other factors that drive a stock’s price, but for our purposes this is the best way I can think of to create accountability and test my thesis. I will revisit how the four $100K portfolios are doing in 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 years.

China Thesis Effect on My Portfolio:

I currently own META -0.15%↓ U 0.00%↑ NET 2.05%↑ AMD 0.00%↑ and INTC -0.05%↓ Both AMD and Intel have significant short-term China revenue exposure, but Intel’s long-term strategy is essentially predicated on China invading Taiwan and then being the semiconductor manufacturer for the rest of the world after TSMC’s leading edge facilities become unusable in Taiwan. AMD on the other hand currently produces most of their chips at TSMC in Taiwan, so war risk to AMD is high. That said, I will be looking to exit my AMD position sometime in the next 2 years prior to what I see as the time-frame for heightened risk for war. Could AMD take their designs to Samsung in South Korea or Intel / TSMC Phoenix in the US for manufacturing in the event of war? They could, but there would be a long line of customers in front of them with more money and negotiating power to get products made in the chaotic aftermath of TSMC no longer taking orders in Taiwan. As the exuberance over AI continues into 2024, and AMD brings more products to market that fulfil AI customer needs, this will provide an opportunity to sell high before systemic risk needs to be fully considered.

Conclusion:

To be a successful long-term stock investor, one needs to be an optimist - and outside of this topic I still am. Despite the gloomy conclusions laid out today, I hope the analysis from this and last week’s article sheds light on why I place such high importance on avoidance of China exposure in my investments. History is not over, and we must contemplate what might formerly be considered unthinkable so that the coming storm can be better weathered.

What do you think? If you made it this far, let me know where you agree or disagree with the thesis and investment advice. Thanks for reading.